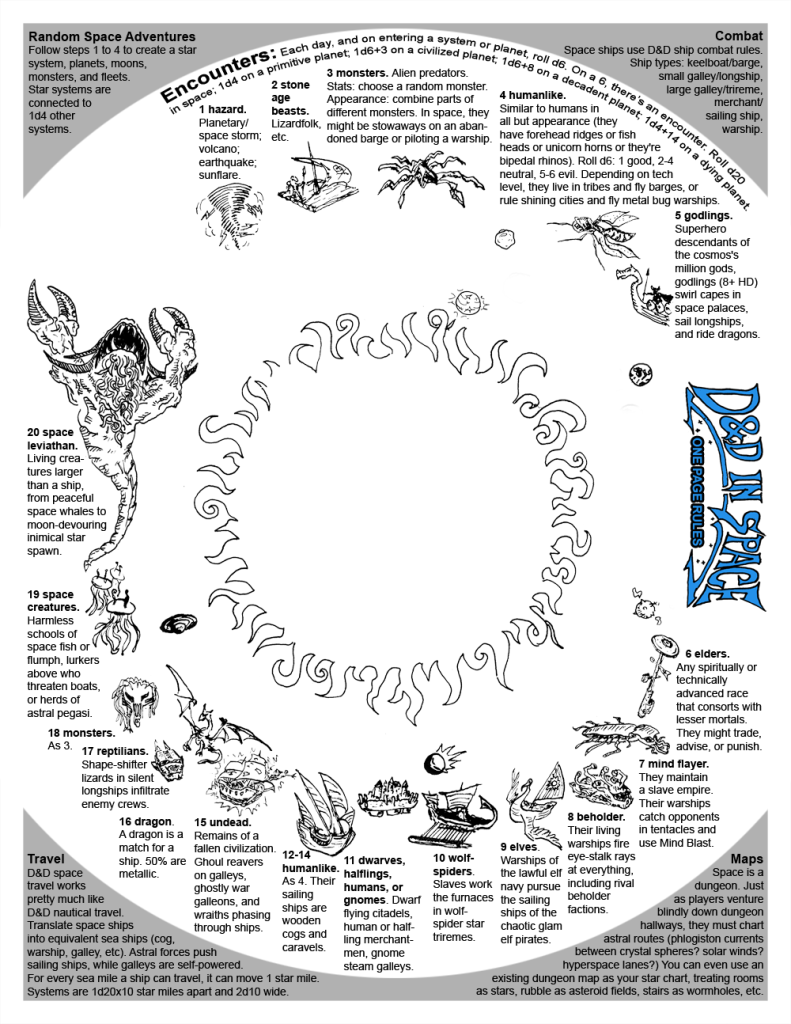

I sometimes run D&D as a planet-hopping space opera, so I need simple space travel rules. I believe that, in order to minimize page flipping, rules systems should fit on one page (with illustrations!). I’ve already started: I’ve come up with star mapping rules and space ship travel/combat rules, and I’ve barely covered the edges of a page!. The next most important question is this: what horrible monsters await you in the void between the stars?

When you’re writing rules for D&D in space, you’ve got to at least consider what Spelljammer has to say. Spelljammer devotes many, many pages to the monsters, dangers, and PC races to be found in space. I want to condense that onto half a page max. I’ll convert all that fluff into crunch by putting it into a random encounter chart. Along with each entry, I’ll explain my game design thinking. The design notes are just for fun, and are not necessary for running the game. Oh, and I’ll draw pictures of all the starships and space monsters on the chart. While I have the pen out, I’ll make a Spelljammer-esque logo for “D&D In Space”.

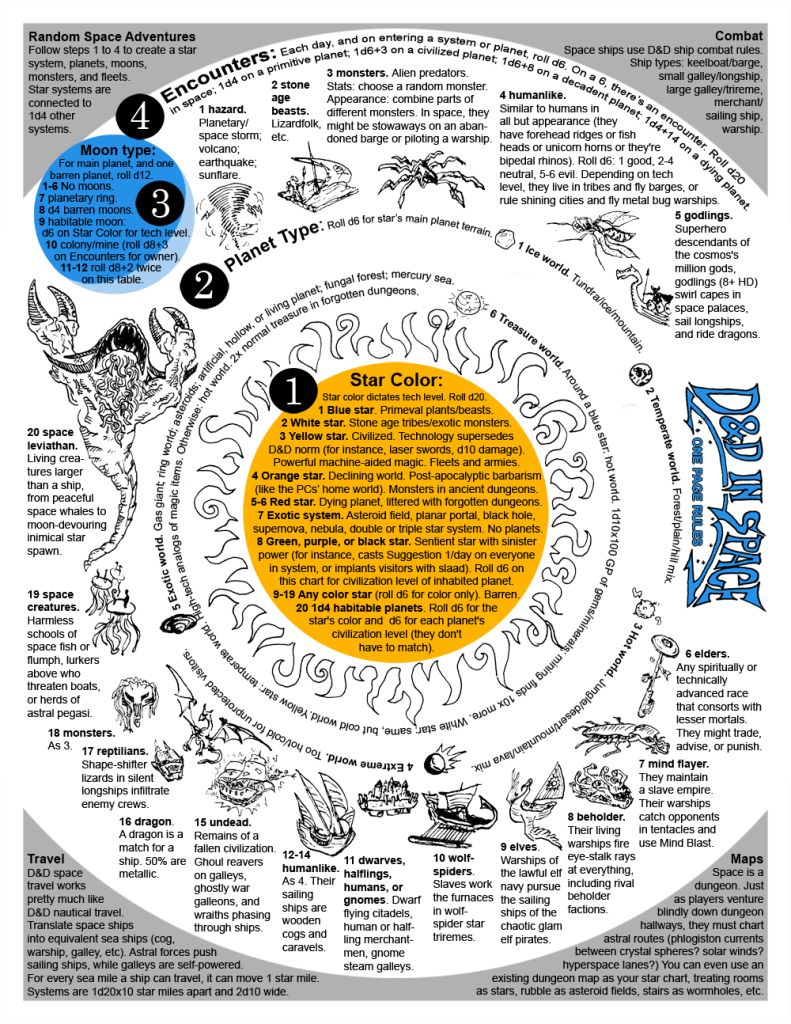

Encounters: Each day, and on entering a system or planet, roll d6. On a 6, there’s an encounter.

To save room, I’ll try to make the same table work for space encounters and encounters on the surface of a planet. I’d also like to have separate encounter probabilities for different types of planets. I’ll make a single chart, with primitive-planet encounters towards the beginning of the chart, advanced in the middle, etc, and then use different dice expressions to generate different encounter types.

Roll d20 in space; 1d4 on a primitive planet; 1d6+3 on a civilized planet; 1d6+8 on a decadent planet; 1d4+14 on a dying planet.

That’s all the rules. Read on for my suggested random encounter chart, and scroll to the end of the page to see the updated and illustrated one-pager.

d20 encounter chart

We’ll start off with weather and natural disasters. Those can happen afloat or on land. On land they’re a very common trope in prehistoric settings.

1 hazard. Planetary/space storm; volcano; earthquake; sunflare.

In Spelljammer, lizardfolk are a surprisingly big deal: despite their relatively low technology, they’re one of the major starfaring races. I don’t see them deserving all that attention, but generalized low-tech anthropomorphic beasties definitely merit 1/20th of the encounters table.

2 stone age beasts. Lizardfolk, etc.

Spelljammer has some good advice for creating alien monsters: use a Monster Manual stat block and change the monster’s appearance. It also has some bad advice: alter trivial parts of the stat block. It suggests doubling or halving the number appearing; adding or subtracting 1 from the AC; and similar undetectable changes. Don’t bother. No one is going to be like “Hey, if this monster’s AC was one higher, I woulda said it was a Mind Flayer!” Just use the original stat block.

I’ll also flog another one of my pet theories here: pokémon as our best representation of alien Lovecraftian terror.

3 monsters. Alien predators. Stats: choose a random monster. Appearance: combine parts of different monsters. In space, they might be stowaways on an abandoned barge or piloting a warship.

Spelljammer asserts that humans are the most common of the starfaring races. This is true in most sci-fi, but I prefer D&D to stick to its Princess of Mars/sword-and-planet roots, in which most dwellers among the stars are humanlike but not human.

Spot 4 on the encounter chart is a overlap area which may be rolled by either 1d4 (on planets more primitive than the D&D standard) or 1d6+3 (for “civilized” planets, i.e. those with higher-than-D&D technology.) Humanlike creatures should be common at both tech levels.

Note: In Spelljammer, there are dozens of pages devoted to the many human-built starships, which are usually shaped like bugs or fish. I’m not sure why this is, but it’s an evocative detail worth preserving.

4 humanlike. Similar to humans in all but appearance (they have forehead ridges or fish heads or unicorn horns or they’re bipedal rhinos). Roll d6: 1 good, 2-4 neutral, 5-6 evil. Depending on tech level, they live in tribes and fly barges, or rule shining cities and fly metal bug warships.

I feel that the galaxy needs a high-level humanoid race. Space-traveling PCs are likely high level, and can’t be lording it over level-1 peons everywhere they go. I’m going to add a new humanlike race to the major races: “godling.” They’re the rich, mighty mortal descendants of the gods of a million prime material planes. They have the stats of humans of character level 8 to 15. I imagine that the various noble godling factions are always warring with each other, especially the scions of good and evil gods. I see them as irritatingly perfect: their heroes are mighty and noble, their villains dastardly, their alliances and treacheries cosmos-shattering, and even their peasants are clean and wise. Now to condense all that gushing into a short sentence:

5 godlings. Superhero descendants of the cosmos’s million gods, godlings (8+ HD) swirl capes in space palaces, sail longships, and ride dragons.

Spelljammer makes up an advanced race of blue giants, the Arcane, who dispense the “spelljammer helms” that allow space travel. That’s a useful role, but very specific to the Spelljammer setting. I want this one-pager to be more of a kit that plugs into the DM’s own setting. If we broaden this category to include all highly-evolved elder races, we make tons of science-fiction stories possible, including like 80% of original Star Trek episodes.

6 elders. Any spiritually or technically advanced race that consorts with lesser mortals. They might trade, advise, or punish.

Mind flayers are one of the big-deal enemies in Spelljammer. This is good. Mind flayers have a sci-fi feel to them, like their appearance in the usual sword-and-sorcery setting is a kind of slumming. Spelljammer mind flayers pilot nautilus-like tentacled space ships.

7 mind flayer. They maintain a slave empire. Their warships catch opponents in tentacles and use Mind Blast.

Beholders are another big Spelljammer enemy: less of a slam dunk than mind flayers, but still solid. Their ships fire large-scale eye-stalk rays. Why not? Disintegration rays seem perfectly at home in a space opera setting. Spelljammer also spends a lot of words on the civil war between the various beholder factions. We don’t have a lot of room here, but we can nod to that.

8 beholder. Their living warships fire eye-stalk rays at everything, including rival beholder factions.

Spot 9 on the encounter chart is another overlap, between 1d6+3 (civilized encounters) and 1d6+8 (decadent encounters). I think of decadent worlds as standard D&D worlds: filled with forgotten dungeons and relics of lost civilizations. D&D elves, who seem like they once had a more sophisticated culture, work in either spot.

Though I don’t like a big human population among the stars, I kind of like the Spelljammer idea of a powerful elven armada. Besides, elves are so central to Spelljammer’s product line that Spelljammer is often described as “elves in space.” Elves stay. Spelljammer actually describes space elves as “effete,” which seems kinda weird: I’d prefer to describe them as “1980s glam.”

9 elves. Warships of the lawful elf navy pursue the sailing ships of the chaotic glam elf pirates.

The neogi, a race of evil wolf/spider/lampreys who sail slave galleys, are another Spelljammer original race. They’re one of two 2nd-edition wolf-spider hybrid monsters, along with the “spyder fiend”, a wolf/spider/tanar’ri. Perhaps both are inspired by the first-edition mention of “Miska the Wolf-Spider.” Chances are you’re not playing 2nd Edition and don’t have neogi stats on hand. I’ll just call these guys “wolf-spiders.” Feel free to use the combat stats of any wolf or spider monster you happen to flip to.

10 wolf-spiders. Slaves work the furnaces in wolf-spider star triremes.

We’ve already said yes to elves in space; surely the other races should get occasional screen time too. After all, Spelljammer took the trouble to come up with lore and space ships for each. I’d like these races to be less common than elves, so I’ll crunch them all into one encounter slot, throw away all of the lore, and make mention of each of their iconic space ships.

11 dwarves, halflings, humans, or gnomes. Dwarf flying citadels, human or halfling merchantmen, gnome steam galleys.

I’ll include the “humanlike” entry again on the chart, because they’re common, and so that they appear in random encounters on “decadent” planets.

12-14 humanlike. As 4. Their sailing ships are wooden cogs and caravels.

Now we head into dying planet encounters (1d4+14). These tend to be from Vancian worlds under red suns, or worlds that have completely fallen to forces of evil or decay.

The first entry is for undead. These encounters tend to be on, or above, nightmare Walking Dead or I Am Legend worlds where the living have been defeated by the dead. Each kind of undead lends its own horror to the proceedings.

15 undead. Remains of a fallen civilization. Ghoul reavers on galleys, ghostly war galleons, and wraiths phasing through ships.

Dragons are solid high-level encounters on alien planets, but they also make great space monsters. They’re powerful enough to challenge ships. Therefore, I’m going to go against Spelljammer lore (which asserts that only its new species, “stellar dragon,” can traverse the phlogiston) and assert that all dragons can fly unassisted in space, and that they search for treasure and lairs all across the universe just as they do in a standard D&D campaign world. I also think that a space setting is better than a standard D&D world as a home for metallic dragons. A gold dragon seems more plausible cavorting through planetary rings under the light of a binary star than it does lording over a few square miles in somebody’s duchy.

16 dragon. A dragon is a match for a ship. 50% are metallic.

For fun, I’m throwing in a non-Spelljammer alien race, the “reptilian“. Some real-world conspiracy nuts, perhaps inspired by the V miniseries, believe that reptilians are a real space-traveling species who live among us, and, in fact, hold key positions in the United States government. In D&D terms, reptilians can be treated as an exotic variant of doppelgangers, but instead of lone opportunists, they’re all agents of a vast conspiracy.

17 reptilians. Shape-shifter lizards in silent longships infiltrate enemy crews.

To fill out the last of the “dying earth” encounters, we’ll throw in monsters again. Because you can never have too many monsters.

18 monsters. As 3.

Spots 19 and 20 are space-only encounters. #19, “space creatures,” is the listing for any of the D&D creatures which might be able to survive on their own in space. I’ve put in some of my own suggestions: I think herds of pegasi galloping through space would be a cool sight, and a herd of flumph, while less majestic, makes more sense in space than it does on a planet. Lurkers Above and other super-weird dungeon monsters might also make just as much sense in space as anywhere else.

19 space creatures. Harmless schools of space fish or flumph, lurkers above who threaten boats, or herds of astral pegasi.

For the last encounter spot, we’ll go for the really big monsters, on the scale of Astral Dreadnoughts or larger. These are monsters at a scale that the PCs can’t generally fight (although, who knows, they might have a Death Star-like vulnerable spot).

20 space leviathan. Living creatures larger than a ship, from peaceful space whales to moon-devouring inimical star spawn.

By now I’ve mostly filled up the one page I’ve allotted for D&D space travel rules. I have some room in the middle of the page to play with, and I still need rules on designing star systems, planets, and moons. I’ll finish those up next week, and I’ll present the finished one-page D&D space travel splatpage.

For now, here’s the one-pager with space travel and random encounter rules:

Flowers and mushrooms are six feet across. Bugs are the size of horses. (Giant bees and ants, with their neat orchards and farms and mighty queens, can be major fey political players.) Trees are redwood sized or larger. Cliffs and mountains brush the moon, which hangs huge and bright in the perennial dusk.

Flowers and mushrooms are six feet across. Bugs are the size of horses. (Giant bees and ants, with their neat orchards and farms and mighty queens, can be major fey political players.) Trees are redwood sized or larger. Cliffs and mountains brush the moon, which hangs huge and bright in the perennial dusk.