I don’t like edition wars, but let’s have a friendly little edition skirmish. Which edition lets you generate the “best” random treasure? I’ll be judging based on variety/unpredictability of treasure, appropriate matching of combat risk and monetary reward, economy of page space, and number of rolls required.

It may seem like a pointless exercise, but I have a reason for it. I want to figure out what I like about previous designs so I can imitate my favorite.

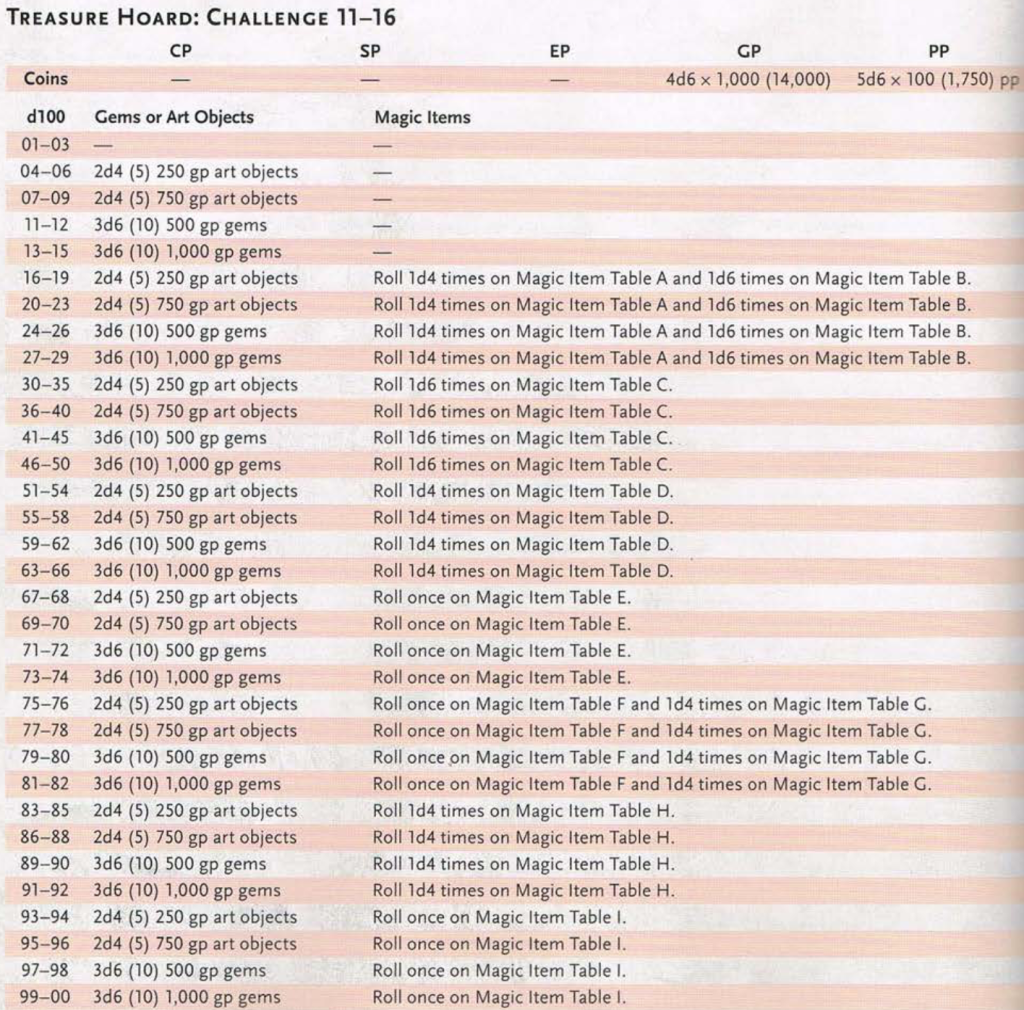

In my last post, I talked at length about how I don’t like the 5e monetary treasure tables. My conclusion: The developers made a decision to limit treasure rolls to a single d100 roll, and that decision led to unvarying, samey treasure, with wide bands of character levels where treasure values don’t increase. Treasure needs to be more varied between levels, and even within a single level.

I plan to make replacement treasure tables for 5e: tables which preserve the quantity of monetary and magical treasure earned over each adventuring tier, but spread it around in a more natural-seeming and satisfying way.

And, as for every bit of rules-mongering that I do, I want it to fit on one printable page. (5e’s tables take up about 3 pages.) More variety than the 5e DMG, in a third the space? It might be a bit tricky. I’d better do some research.

So, did other editions do any better at letting you roll up interesting, varied, inspiring treasure? I’m not primarily considering magic items here – just the coins and other forms of nonmagical wealth.

first and second edition

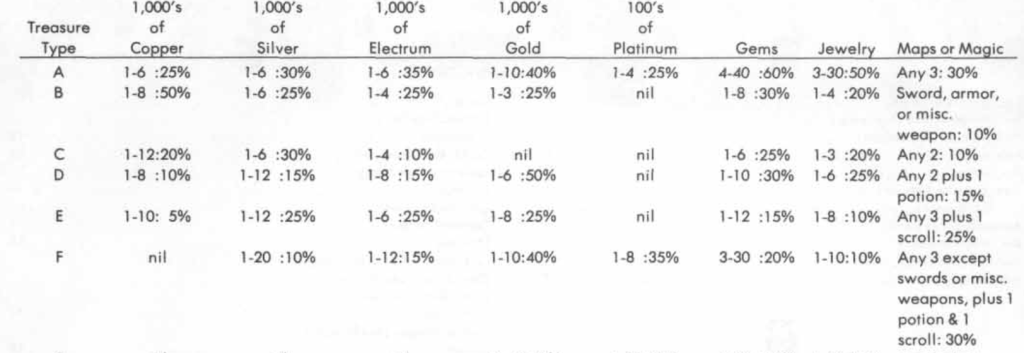

Even if you never played 1e, or one of the other TSR versions of D&D, it will probably come as no surprise that its treasure system was a complex, nonsystematic edifice that seemed less like it was designed and more like it evolved. There was no explicit concept of wealth by level in 1e (though since 1 gp = 1 xp, your earned money was roughly equal to your earned xp). There were no treasure charts by level. Instead, there were 26 “treasure types”, labeled A through Z, with no explicit guidance about what each was for. Each monster had a bespoke, customized treasure entry in the monster manual containing zero or more treasure type codes. For instance, hobgoblin treasure is “individuals J, M, D, Q (x5) in lair”. (It’s either treasure or it’s subway directions. J to M to D to Q will get you from JFK airport to my house in Brooklyn.) Generally (but with many exceptions) stronger monsters had more treasure, but in a more naturalistic than mathematical way.

I love how treasure is story-driven with this method. Pirates have rich treasure plus a treasure map! Xorn have a lot of gems! Dragons have a little of everything! The only disadvantage, if it is a disadvantage, is that the intended pace of treasure acquisition was not clear to DMs, and therefore in gp=xp systems, the intended pace of leveling wasn’t made explicit.

The 1e system could require a lot of die rolling for big treasures. On average, for instance, Treasure Type A requires about 20 to 25 rolls, minus any required for figuring out what gems you had. (Let’s assume you didn’t roll separately for all 4-40 gems.) Is this extra work a problem? I mean, it’s not a show-stopper. Generally, keeping the game moving is a plus, but treasure generation might be an exception to that rule. Farm it out to the players! They’ll be happy to do it.

What the 1e treasure matrix loses in economy of die rolls, it gains in economy of space. It takes up a single page in the monster manual! Very tidy.

So that’s first edition. The second edition system is just like first, with a few values moved around, so I won’t treat it separately.

Overall grade: A

Third edition

Third edition was the first time D&D had a rigorous and transparent treasure system designed to get characters the right amount of treasure at each level. Each level had a different set of treasure tables with smoothly ascending cash values. Furthermore, within each level there were variations: at level one, for instance, you might find copper OR silver OR gold OR platinum, with a wide range of possible values for each. (But never two types of coinage together, oddly, unless you lump several treasure rewards together.)

The rigorous, explicit nature of 3e treasure might not appeal to every DM, but as a tinkerer I appreciate it. If I wanted to make up a treasure or reward on the fly for a group of 4th level characters, it’s easy to extrapolate a reasonable value: compare that to 1e, where I have no idea what’s a good-sized treasure for a 4th-level party.

The third edition charts are tidy. They all fit on one or two pages, depending on printing, from level 1 all the way to level 30 (though level 30 is absurdly unusable: same as level 20 but with an additional forty-two major magic items. Still. Pretty good for one page of charts!)

It also required fewer die rolls than the 1e chart, at least at low to mid levels. Instead of rolling on an eight-column matrix, as in 1e, you roll on a three-column matrix. For level 11, for instance, the maximum number of rolls you can make is ten, excluding gem subtables but including magic item determination. Obviously, at level 30, you’ll need at least 42 more rolls for all those major magic items. But I think we can agree they printed that line as a joke and ignore it.

There’s one more thing I like a lot in 3e: it’s the only edition with a “mundane items” table in the treasure section. Especially at early levels, there’s room for useful, expensive items as a treasure reward. The Mundane Items table included expensive armors, masterwork weapons, alchemist’s fire, and the like. It provided upgrades for low-level characters while keeping magic items rare – and also buffed monsters. Kobolds with plate armor and alchemists’ fire are no joke.

Grade: A

Fourth edition

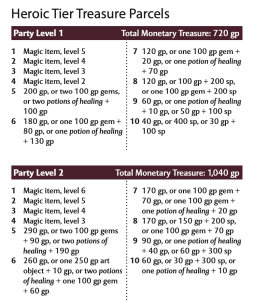

Like third edition, fourth edition had a cash reward progression which increased smoothly every level – better than the big 5e tier-sized blocks of identical treasure. (In 5e, you have exactly the same expected treasure from a CR 5 encounter as from a CR 10 one.) 4e also had nice, organic-seeming groupings of treasure of the kind that you can’t get in 5e. For instance, in 4e, you could find a magic item with no coins; or reasonable-sized groups of one or two gems instead of 5e’s bunches of 7 at a time; or a treasure consisting only of gems.

Fourth edition’s 20 charts took up three and a half pages: about the same amount of space as is required for 5e’s four charts. Not too bad.

And I believe 4e is the edition that came up with the idea of leveled grades of gems. In previous editions, a gem was a gem was a gem – identical to any other until you rolled on a separate chart to determine its value. For instance, in third edition, at level 1 you have a 5% chance of finding one gem, and at level 20 you have a 35% chance of finding 4d10 gems. But a gem found at any character level had the same average value. Even at level one, you might roll high on the gem table and get a 5,000 gp diamond.

That appeals to the gambler in me, but the 4e way is more buttoned-down. At low levels, you found onyx, and at high levels you found star rubies and astral diamonds.

So the 4e system had a lot going for it! However, there was one slight problem. 4e didn’t actually have a system for random treasure. There were no tables to roll on: you selected from fixed-value “treasure packets” for each level. Individual treasures were quite varied, but the amount of treasure per level was completely predetermined. So as decent as 4e’s treasure handouts were, we can’t use them as a guide for making new random treasure charts.

Grade: Incomplete

Fifth Edition

I cover 5e exhaustively here and it gets a C.

and the winner is…

Much as I love the treasure-type system of the early editions, I think the third edition treasure tables are my favorite. There’s an argument to be made either way. You might prefer the esoteric and monster-story-driven treasure types of 1e to the mathematical precision of 3e. 4e (no random treasure) and 5e (unvaried magic treasure) are decidedly inferior to those two.

can we improve 5e?

In my next post, I’ll build a new treasure table for fifth edition, using third edition as my jumping-off point. It’ll offer varied treasure, with different payouts for each level, and it’ll grant the same amount of overall treasure as the current 5e tables do. As a bonus, I want to make it compatible with very large or small adventuring parties (no edition’s treasure tables were designed with solo play in mind). And I’ll add mundane treasure.

If possible I’d like it to fit on one page, so you can print it out and tape it in the back of your DMG. Not guaranteeing a huge font though!

I’ll also build these rules as an option into my Inspiration app, so you can have better treasure when you’re DMing from your phone.