There’s about a day left in Autarch’s Adventurer Conqueror King: Domains at War kickstarter. I was lucky enough to get a Domains at War war-game playtest with Tavis Allison. It’s very impressive for the same reason Adventurer Conqueror King is impressive: it marries simple D&D mechanics with rock-solid behind-the-scenes mathematical rigor. That may not sound like much, but that combination is a rock on which many RPG-design ships have foundered. I still can’t believe that ACKS has pulled it off, and I keep peeking behind the curtain, only to find that the system is even more solid than I expect.

There’s about a day left in Autarch’s Adventurer Conqueror King: Domains at War kickstarter. I was lucky enough to get a Domains at War war-game playtest with Tavis Allison. It’s very impressive for the same reason Adventurer Conqueror King is impressive: it marries simple D&D mechanics with rock-solid behind-the-scenes mathematical rigor. That may not sound like much, but that combination is a rock on which many RPG-design ships have foundered. I still can’t believe that ACKS has pulled it off, and I keep peeking behind the curtain, only to find that the system is even more solid than I expect.

Let me tell you two stories: the first is why you should have ACKS on your bookshelf, and the second is why you should back Domains at War right now.

Ask Adventurer Conqueror King: How many knights per square mile?

Right now I’m reading Charles Oman’s A History of the Art of War, a giant volume that, according to Jon Peterson, was a primary text for Gary Gygax’s Chainmail. I’m reading a chapter chock full of the meaty medieval economic information I love:

We have seen that “knight-service” and “castle-ward” were ideas not altogether unfamiliar before the Conquest, and that the obligation of every five hides of land to send a mailed warrior to the host was generally acknowledged […] A landholder, knowing his servitium according to the assessment of the vetus feoffamentum of the Conqueror, had to provide the due amount of knights. This he could do, in two ways: he might distribute the bulk of his estate in lots roughly averaging five hides to sub-tenants, who would discharge the knight-service for him, or he might keep about him a household of domestic knights, like the housecarles of old, and maintain them without giving them land. Some landholders preferred the former plan, but some adhered, at least for a time, to the latter. But generally an intermediate arrangement prevailed: the tenant-in-chief gave out most of his soil to knights whom he enfeoffed on five-hide patches, but kept the balance in dominio as his private demesne, contributing to the king for the ground so retained the personal service of himself, his sons, and his immediate domestic retainers.

OK, this seems pretty clear: each knight needs five hides of land to support him. Problem is, what’s a hide? Apparently, it’s an extremely variable amount: the land needed to support one farming family. Its area is most often given in old texts as 120 acres.

OK, this seems pretty clear: each knight needs five hides of land to support him. Problem is, what’s a hide? Apparently, it’s an extremely variable amount: the land needed to support one farming family. Its area is most often given in old texts as 120 acres.

Given this information, I extrapolated two useful pieces of information: how many families can be supported by a square mile of farmland, and how many knights defend it? (Stuff like this can be very useful for D&D worldbuilding, whether you need to know, for instance, the size of a country’s army or, conversely, the size of the country needed to support the army you want to use.) According to my initial calculations, a square mile of farmland, 640 acres, contained about 5 hides: about 5 farming families and one knight.

I thought I’d compare this to ACKS. I discovered that each hex of civilized land contains, according to ACKS, about 4x as many peasant families as I expected. I had a feeling that Autarch hadn’t missed a trick here. I emailed Tavis and Alex to see if they could unravel this riddle for me. Alex responded:

It’s quite confusing because a hide is not a fixed area of land. It’s 60-120 acres, but the acres in question are “old acres”. ACKS uses “modern acres”. A hide is about 30 modern acres. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_medieval_land_terms. […] Now, 1 6-mile hex is about 32 square miles, which is 20,480 acres, which translates into 682 peasant families. At sufficient densities I assume a surplus that includes non-farming craftsmen, so we end up with the cap of 750 families per 6-mile hex in ACKS.

In any event, 5 hides supports 5 families in ACKS. Each peasant family generates on average 12gp per month in revenue for their lord. 5 x 12 gp = 60gp. The monthly cost for a knight is 60gp (see Mercenary Wages, Heavy Cavalry). So each 5 hides can support 1 knight, as per The Art of War in the Middle Ages.

Mystery solved! My estimate for peasants per mile was off by a factor of 4 because the area of an acre had increased 4x! Furthermore, I was delighted to see that five families exactly supported one knight, as Oman suggested.

That’s one of the big selling points of ACKS for me. I like to do historical research and tweak my game accordingly, but if I want to double-check my answers, having ACKS on my shelf makes things easier. And if I consistently fall back on its prices, domain rules, end economic model, I’ll end up with something more plausible than what I could cobble together on my own.

Domains at War: Richard and Saladin

A few nights ago I went over to Tavis’s house for a playtest of the Domains at War system. I hadn’t read the rules, but I was deep in Oman’s descriptions of the major battles of the Crusades, and I’ve read a lot about medieval tactics. I figured that my ignorance of the Domains at War rules was actually a boon for the playtest. If I could command an army using only the tactics described in historical battles, and get plausible results, without knowing rules, that would be a win for the system.

A few nights ago I went over to Tavis’s house for a playtest of the Domains at War system. I hadn’t read the rules, but I was deep in Oman’s descriptions of the major battles of the Crusades, and I’ve read a lot about medieval tactics. I figured that my ignorance of the Domains at War rules was actually a boon for the playtest. If I could command an army using only the tactics described in historical battles, and get plausible results, without knowing rules, that would be a win for the system.

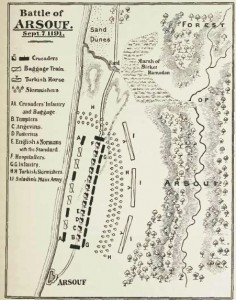

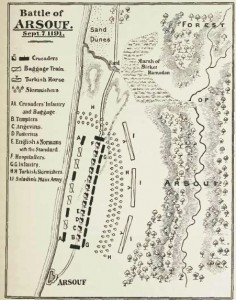

On the train ride over, I’d been reading about the battle of Arsouf between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. I think Tavis had some other playtest planned, but after I enthusiastically recounted the battle, he said, “That sounds fun: let’s play that.” Oman gives a rather detailed troop breakdown of both sides, including the generals in charge of various divisions of the Crusaders. D@W includes rules for subcommanders, each with their own initiative and attributes, so the wings of my army were led by their historical commanders: King Richard at the center, King Guy of Jerusalem in the rear, and the Duke of Burgundy in the van. I put the Bishop of Bauvais, a cleric, at the head of the small band of heavily-armed Templars at the fore. Although D@W includes rules for battlefield heroics by PCs, King Richard and Saladin never met for a decisive D&D-encounter showdown.

The Battle of Arsouf is exceptional because the Crusaders, for once, held their ground and stuck to their game plan instead of charging disastrously into traps set by Saladin’s more mobile cavalry. I set myself the same challenge: could I maintain discipline and resist the temptation to charge Tavis’s skirmishers?

The Battle of Arsouf is exceptional because the Crusaders, for once, held their ground and stuck to their game plan instead of charging disastrously into traps set by Saladin’s more mobile cavalry. I set myself the same challenge: could I maintain discipline and resist the temptation to charge Tavis’s skirmishers?

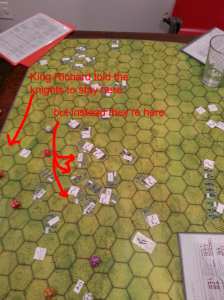

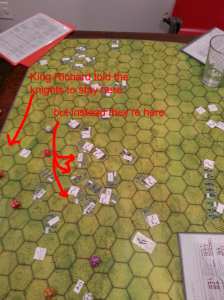

NO!

After a few turns of being peppered by arrows, I deviated from King Richard’s strategy. I saw an opportunity to send my cavalry into the flank of Saladin’s wheeling cavalry. It was worth it to see how beautifully my rolling cavalry charge checked Tavis’s advance and sent a few of his units fleeing for the woods.

After a few turns of being peppered by arrows, I deviated from King Richard’s strategy. I saw an opportunity to send my cavalry into the flank of Saladin’s wheeling cavalry. It was worth it to see how beautifully my rolling cavalry charge checked Tavis’s advance and sent a few of his units fleeing for the woods.

After a few turns of opposed cavalry charges and countercharges, I was rolling up Tavis’s left wing while my own left wing was close to routing. We’d each taken a lot of casualties. Tavis needed to kill only one more of my units to force a potentially game-ending morale check; I needed two. And in real life, it was well after midnight. We played one more turn. On my left wing, Saladin concentrated his forces on one of King Guy’s cavalry units, trying to force it to flee, but it held. Meanwhile, on my right wing, I chased down and defeated one of Saladin’s light cavalry units, and sent a thundering charge into a second, but, bad luck for me, it made its morale check. Night fell on the battlefield, ending the battle inconclusively after a tense final turn. I got home around 3 AM on a work night – the sign of a good game.

As the game went on, I found myself trusting the rules more and more. If I had just role-played the part of King Richard, I think the game system would have given me the victory. In fact, I role-played the part of an undisciplined, impetuous Crusader cavalier, and, as they so frequently did, I nearly turned victory into defeat. Maybe Tavis will give me a rematch sometime. This time I’ll stick to the plan.