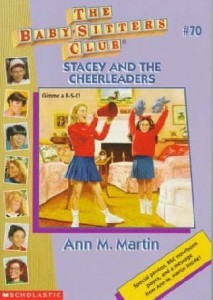

Last week, I met a challenge to my Every Book’s a Sourcebook project: find D&D inspiration from the text of a Babysitters Club book. I read BSC #70, Stacey and the Cheerleaders, and used it to generate a great idea for a village heist adventure.

Last week, I met a challenge to my Every Book’s a Sourcebook project: find D&D inspiration from the text of a Babysitters Club book. I read BSC #70, Stacey and the Cheerleaders, and used it to generate a great idea for a village heist adventure.

To prove how easy it is, here is a BONUS idea from Stacey and the Cheerleaders:

They stood there like statues, the goddesses of Gloom and Doom.

I think this quote describes some kids Stacey is babysitting; but what awesome statues it describes! Truly Anne M. Martin is a master fantasy world-builder.

The goddesses Gloom and Doom are the twin daughters of Lord Poison, the Dark Hand of Death. Their monumental white statues, mottled with red moss, stand at the entrance of Blood Pass. Travellers who enter Blood Pass offer fearful prayers to the goddesses. Nevertheless, sometimes a statue’s eyes flash, and a curse falls upon a traveller.

Whenever anyone enters Blood Pass, roll 2d20, one for each sister.

On a 1 on the first die, the traveller falls under the Curse of Gloom. From now on, every hour, the traveller must make a saving throw. If the traveller fails, he or she sinks into an hour-long Gloom, during which he or she will make no unassisted actions except to sit or lie down. If forced to walk, the Gloomy traveller is Slowed. A Gloomy traveller will resist being put on horseback, and will dismount at the earliest oppportunity. If attacked, a Gloomy traveller will do nothing but take the total defense action. The curse lifts after 24 hours have passed.

On a 1 on the second die, the traveller falls under the Curse of Doom. From now on, the traveller will lose one healing surge (or 1/4 of total HP) an hour. The only way to lift the curse is to arrive at the other end of Blood Pass, which takes ten hours of hard travel.

Worst-case scenario is that someone in the party receives a Gloom, slowing travel, and someone receives a Doom, providing serious consequences for delay. But, hey, that’s what you get for taking a cursed shortcut through the mountains.